Minimax

A game can be thought of as a tree of possible future game states. The current state of the game is the root of the tree (drawn at the top). In general this node has several children, representing all of the possible moves that we could make. Each of those nodes has children representing the game state after each of the opponent’s moves. These nodes have children corresponding to the possible second moves of the current player, and so on. The leaves of the tree are final states of the game: states where no further move can be made because one player has won, or perhaps the game is a tie.

Search

Suppose that we assign a value of positive infinity to a leaf state in which we win, negative infinity to states in which the opponent wins, and zero to tie states.

Usually expanding the entire game tree is infeasible because there are so many possible states. The solution is to only search the tree to a specified depth. Define and evaluate function (the static evaluator) returns a value between $-\infty$ and $\infty$ for game positions that are not final positions. For game positions that look better for the player, it returns larger numbers, for game positions that look better for the opponent (look bad for the player) it returns small numbers (negatives too). When the depth limit of the search is exceeded, the static evaluator is applied to the node as if it were a leaf:

If we can traverse the entire game tree, we can figure out whether the game is a win for the current player assuming perfect play: we assign a value to the current game state by we recursively walking the tree. At leaf nodes we return the appropriate values (either declare win $\infty$/loss $-\infty$ or the result of evaluate). At nodes where we get to move, we take the max of the child values because we want to pick the best move; at nodes where the opponent moves we take the min of child values because we assume perfect play on the part of the opponent and they’ll pick the smallest number. This gives us the following schematic evalution of a game tree

and the following pseudo-code procedure for minimax evaluation of a game tree (remember the player is trying to drive the score positive and the opponent is trying to drive the score negative):

def minimax(n: node, depth: int, max_depth: int) -> int:

if leaf(n) or depth == max_depth: return evaluate(n)

if is_max_node(n):

value = $-\infty$ # initialization for max

for each child of n:

value = max(value, minimax(child, depth+1, max_depth))

elif is_min_node(n):

value = $\infty$ # initialization for min

for each child of n:

value = min(value, minimax(child, depth+1, max_depth))

return value

Alpha-beta pruning

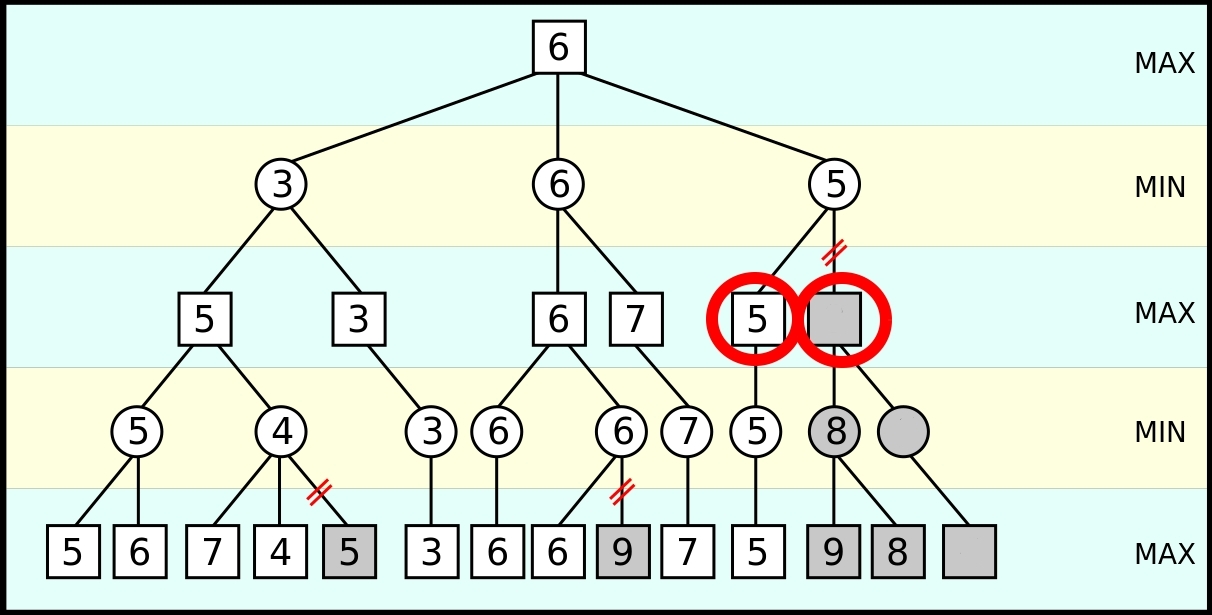

The full minimax search explores some parts of the tree it doesn’t have to: for example in this game tree

Keep in mind that the opponent chooses minimum amongst children and player choose maximum amongst children.

In the right most subtree it’s known that so far (as far as the subtree has been explored) the best that the opponent can do is a 5. As the player (not the opponent) is evaluating moves/game-outcomes (below gray square) they discover they can make a move that’s worth 8. It’s at this point the player can stop exploring because the opponents choice has already been made, seeing as has how the opponent is trying to minimize amongst children (therefore will never pick the 8 over the 5) and seeing as how the player themselves is trying to maximize amongst the children (therefore will pick at least that 8).

Therefore the heuristic to prune by calls for keeping track of $\alpha$, the maximum value seen so far amongst the children by the player, and $\beta$, the minimum value so far seen amongst the children, and stopping the search if ever $\alpha \geq \beta$.

That leads to this pseudo-code for minimax with alpha-beta pruning:

def minimax_ab(n: node, depth: int, max_depth: int, $\alpha$: int, $\beta$: int) -> int:

if leaf(n) or depth == max_depth: return evaluate(n)

if is_max_node(n):

value = $-\infty$ # initialization for max

for each child of n:

value = max(value, minimax_ab(child, depth+1, max_depth, $\alpha$, $\beta$))

if value $\geq \beta$: break # will never get picked by opponent

$\alpha$ = max($\alpha$, value)

elif is_min_node(n):

value = $\infty$ # initialization for min

for each child of n:

value = min(value, minimax_ab(child, depth+1, max_depth, $\alpha$, $\beta$))

if $\alpha \geq$ value: break # will never get picked player

$\beta$ = min($\beta$, value)

return value

Alternative (slicker) implementation

def minimax_ab(node, depth, max_player, $\alpha$, $\beta$):

if depth == 0: return evaluate(node)

if max_player:

value = $\alpha$

for each child of node:

value = max(value, minimax_ab(child, depth-1, max_player, value, $\beta$))

if value $\geq \beta$: break

else:

value = $\beta$

for each child of node:

value = min(value, minimax_ab(child, depth-1, max_player, $\alpha$, value))

if $\alpha \geq$ value: break

return value

Max-min inequality

Imagine a continuous zero-sum game with two players: if the first player chooses $w$ and the second player chooses $z$, then the first player pays an amount $f(w,z)$ to the second player. Player 1 therefore wants to minimize $f$, while player 2 wants to maximize $f$.

Suppose that player 1 makes the first choice $w_0 \in W$ and then player 2 makes a choice, after learning of player 1’s choice. Since player 2 wants to maximize $f(w_0,z)$ they will choose $z_0\in Z$ that maximize $f(w_0, z)$. The resulting payoff will be $\sup_{z\in Z} f(w_0, z)$, which depends on $w_0$, player 1’s choice. Player 1 knows (or assumes) player 2 will follow this (optimal) strategy, and so will choose $w_0 \in W$ to make this worst-case payoff to player 2 as small as possible, i.e.

\[w_0 = \operatorname*{argmin}_{w\in W} \sup_{z \in Z} f(w,z)\]which results in the payoff

\[\inf_{w\in W} \sup_{z \in Z} f(w,z)\]from player 1 to player 2. Now suppose the order of play is reversed: player 2 must choose $z \in Z$ first, and then player 1 chooses $w \in W$ (with knowledge of $z$). Following a similar argument player 2 should choose to maximize $\inf_{w\in W} f(w,z)$, which results in a payoff of

\[\sup_{z \in Z} \inf _{w \in W} f(w,z)\]The max-min inequality states the (intuitively obvious) fact that it is better for a player to go second, or more precisely, for a player to know their opponent’s choice before choosing. In other words, the payoff to player 2 will be larger if player one must choose first.

\[\sup _{z}\inf _{w}f(w,z)\leq \inf _{w}\sup _{z}f(w,z)\]Minimax theorem

Let ${\displaystyle W\subset \mathbb {R} ^{n}}$ and ${\displaystyle Z\subset \mathbb {R} ^{m}}$ be compact convex sets. If ${\displaystyle f:W\times Z\rightarrow \mathbb {R} }$ is a continuous function that is convex-concave, i.e. ${\displaystyle f(\cdot ,z):W\rightarrow \mathbb {R} }$ is convex for fixed ${\displaystyle z}$, and ${\displaystyle f(w,\cdot ):Z\rightarrow \mathbb {R} }$ is concave for fixed ${\displaystyle x}$ (i.e. a saddlepoint).

Then we have that

\[{\displaystyle \min _{x\in X}\max _{y\in Y}f(x,y)=\max _{y\in Y}\min _{x\in X}f(x,y)}\]i.e. neither player has any advantage in terms of going first or second.