Byzantine Broadcast

- Introduction

- Dolev-Strong Protocol

- Lower bound without digital signatures (for agreement)

- Upper bound without digital signatures (for broadcast)

- Footnotes

Introduction

“Imagine that several divisions of the Byzantine army are camped outside an enemy city, each division commanded by its own general. The generals can communicate with one another only by messenger. After observing the enemy, they must decide upon a common plan of action. However, some of the generals may be traitors, trying to prevent the loyal generals from reaching agreement.”1

Formal definition of Byzantine Broadcast

Consider a distributed system of \(n\) nodes with one node identified as the designated sender (or sender). WLOG the first node is the sender. The set of all nodes is written \([n] := \{1, \dots, n\}\). Nodes that follow a prescribed protocol throughout an instance are called honest (or correct) and those that need not follow the protocol are called corrupt. It need not be known which nodes are corrupt. All corrupt nodes can share information with each other; therefore, it is sensible to imagine all corrupt nodes as controlled by a single adversary. We also assume that the set of corrupt nodes is chosen prior to the start of the protocol and remains static, as opposed to changing through out an instance (adaptive).

We assume that every pair of nodes can communicate and the existence of public key infrastructure (PKI) i.e. that nodes can sign messages with cryptographic signatures (thereby verifying the authenticity of the messages). We use the notation \(\langle m \rangle_i\) for the pair \((m, \sigma_i(m))\) where \(m\) is a message and \(\sigma_i(m)\) is a valid signature for the message that can be verified using node \(i\)’s public key.

A synchronous network is one for which messages sent by honest nodes are guaranteed to be received by honest recipients within a finite amount of time (called a round). Thus, a protocol proceeds in rounds.

At the beginning of a protocol the sender receives an input bit \(b \in \{0,1\}\). The nodes then run the protocol and at the end every node outputs a bit. A Byzantine Broadcast (BB) protocol satisfies the following two requirements irrespective of how the corrupt nodes behave

- Consistency: if two honest nodes report \(b\) and \(b'\) then \(b = b'\)

- Validity: if the sender is honest and receives input \(b\), then all honest nodes report \(b\) as well.

Dolev-Strong Protocol

Assume each node \(i\) maintains a set \(\mbox{extr}_i\), called the extracted set, of the distinct bits it has received so far. We use \(\langle b \rangle_S\) to denote the message \(b\) with attached valid signatures on \(b\) from \(S \subseteq [n]\). Let \(f\) be the upper bound on the number of corrupt nodes. The Dolev-Strong Protocol is defined as follows:

- Round 0: the sender sends \(\langle b \rangle_1\) to every node.

- Rounds \(r = 1, \dots, f+1\): for every message \(\langle b' \rangle_{1, j_1, j_2, \dots, j_{r-1}}\) that node \(i\) receives with \(r\) distinct signatures (including the sender):

- If \(b' \notin \mbox{extr}_i\), then add \(b'\) to \(\mbox{extr}_i\) and send \(\langle b' \rangle_{1, j_1, j_2, \dots, j_{r-1}, i}\) to everyone at the beginning of the next round (notice the addition of \(i\) to \(\langle b' \rangle_{1, j_1, j_2, \dots, j_{r-1}, i}\)).

- If \(b' \in \mbox{extr}_i\) do nothing.

- At the end of round \(f+1\) for each node \(i\):

- If \(\lvert \mbox{extr}_i \rvert = 1\), then output the bit in \(\mbox{extr}_i\)

- If \(\lvert \mbox{extr}_i \rvert \neq 1\), then output 0.

Claim: The Dolev-Strong protocol is a Byzantine Broadcast protocol.

Lemma 1: Let \(r \leq f\). If by the end of round \(r\), some honest node \(i\) has \(b'\) in its extracted set, then by the end of round \(r+1\) every honest node has \(b'\) in its extracted set.

Proof: Since node \(i\) has \(b'\) in its extracted set, \(b'\) must have been added in some earlier round \(t \leq r \leq f\). In this round \(t\), node \(i\) received \(\langle b' \rangle_{1, j_1, j_2, \dots, j_{t-1}}\) with \(t\) distinct signatures (including one from the sender) and none of these signatures were node \(i\)’s (for otherwise node \(i\) would received the message on some \(t' < t\), contradicting minimality). Therefore node \(i\) sent out \(\langle b' \rangle_{1, j_1, j_2, \dots, j_{t-1}, i}\) in round \(t+1\). Thus by our synchrony assumption, all other honest nodes will receive this messages with \(t+1\) distinct signatures at the beginning of round \(t+1 \leq r + 1\) and will, therefore, add \(b'\) to their extracted sets in round \(t+1 \leq r+1\) (if it has not already been added).

Lemma 2: If some honest node \(i\) has \(b'\) in its extracted set by the end of round \(f+1\), then every honest node has \(b'\) in its extracted set by the end of round \(f+1\).

Proof: Consider the two following cases:

- Case 1: Node \(i\) first added \(b'\) to its extracted set in round \(r < f+1\). By Lemma 1, every other honest node has \(b'\) in its extracted set by round \(r+1 \leq f+1\).

- Case 2: Node \(i\) first added \(b'\) to its extracted set in round \(r = f+1\). For this to happen, node \(i\) must have received \(f+1\) distinct signatures on \(\langle b' \rangle_{1, j_1, j_2, \dots, j_{f}}\). Since at most \(f\) nodes are corrupt there was one honest node amongst the \(\{1, j_1, j_2, \dots, j_{f}\}\) that received \(b'\) in an earlier \(r < f+1\) round. Therefore, again by Lemma 1, every honest node (including node \(i\)) would have added \(b'\) to its extracted set by the end of round \(r+1 \leq f+1\).

Proof that Dolev-Strong protocol is a Byzantine Brodcast protocol: By Lemma 2, all honest nodes have the same extracted set at the end of round \(f+1\), and thus consistency is achieved. Validity follows from the fact that no one can forge the sender’s signature (and therefore no other \(\langle b' \rangle_{1, j_1, j_2, \dots, j_{f}}\) could have been received by honest nodes other than \(\langle b \rangle_{1, j_1, j_2, \dots, j_{f}}\)).

Note that every node sends at most two values to all other nodes, and each value may contain \(O(f)\) signatures. Therefore the total communication is \(O(n^2 f)\).

Lower bound without digital signatures (for agreement)

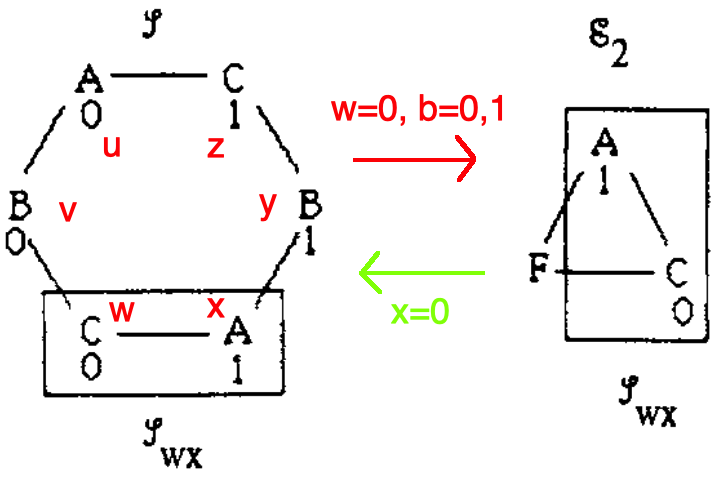

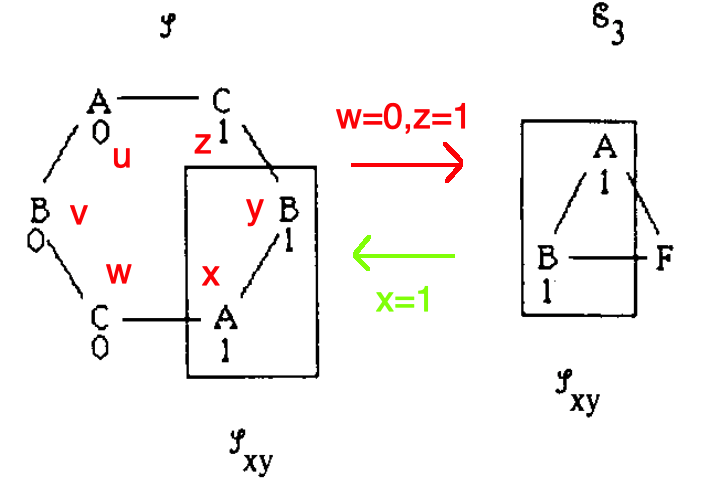

Pictures stolen from the original Fisher, Lynch, and Merritt, 1985 paper.

How integral was PKI to the Dolev-Strong protocol?

Claim: Without digital signatures if \(f \geq n/3\) of nodes are corrupt then Byzantine agreement2 is impossible.

To prove this, we first need to state two assumptions.

Locality axiom: Let \(\mathscr{G}, \mathscr{G}'\) be two systems (nodes and communication edges) with behaviors3 \(\mathscr{E}, \mathscr{E}'\) and isomorphic subsystems \(\mathscr{U}, \mathscr{U}'\) (with corresponding vertex sets \(U, U'\)). If the corresponding behaviors of the inedge borders of \(U,U'\) in \(\mathscr{E}, \mathscr{E}'\) are identical, then the scenarios4 \(\mathscr{E}_{\mathscr{U}}, \mathscr{E}'_{\mathscr{U}'}\) are identical.

That is to say, communication only happens across communication edges.

Fault axiom: Let \(A\) be any device5 and let \(E_i\) be some edge behavior of a node running \(A\), such that each \(E_i\) is the behavior of the \(i\)th outedge in some system behavior \(\mathscr{E}_i\). Let \(u\) be a node with outedges \((u, v_i)\). Then there is a device \(F\) such that in any system in which \(u\) runs \(F\), the behavior of each outedge \((u, v_i)\) is \(E_i\).

This enables faulty nodes to present any behavior that a correct node can present over different edges during different system behaviors but simultaneously, i.e during a single run.

Proof: Suppose there is a protocol P that can achieve Byzantine agreement with three fully connected parties \(a, b, c\) that run devices \(A, B, C\).

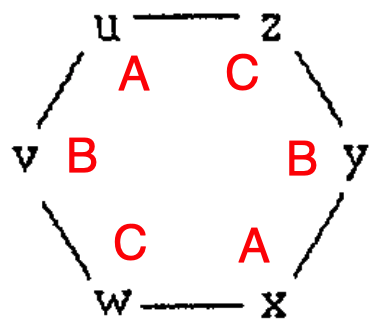

Consider their covering graph6

where \(\phi(u) = \phi(x) = A\) and \(\phi(v) = \phi(y) = B\) and \(\phi(w) = \phi(z) = C\).

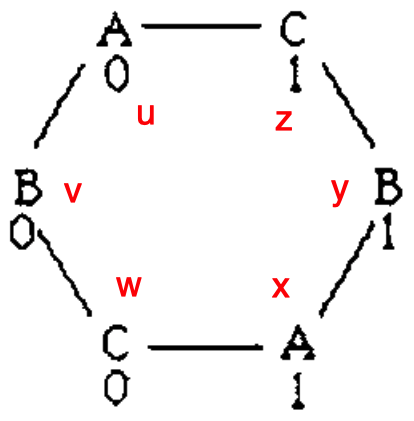

Now let the system start with inputs as such

i.e. \(u\) runs device \(A\) with input 0, \(v\) runs device \(B\) with input 0, and so on. Let \(\mathscr{L}\) be the resulting behavior of this surrogate system. We will see that this set of inputs corresponds to three valid scenarios in the “covered” system but that the “covered” system imposes conditions on this system that lead to a contradiction.

Consider three scenarios for this surrogate system \(\mathscr{L}_{v w}, \mathscr{L}_{wx}, \mathscr{L}_{x y}\). We argue each corresponds directly with a correct behavior of \(\mathscr{E}_i \in\) P. We then derive a contradiction in \(\mathscr{L}\) thereby showing that P cannot solve Byzantine agreement.

Note that red arrows mean inputs while bright green mean decisions.

Scenario 1

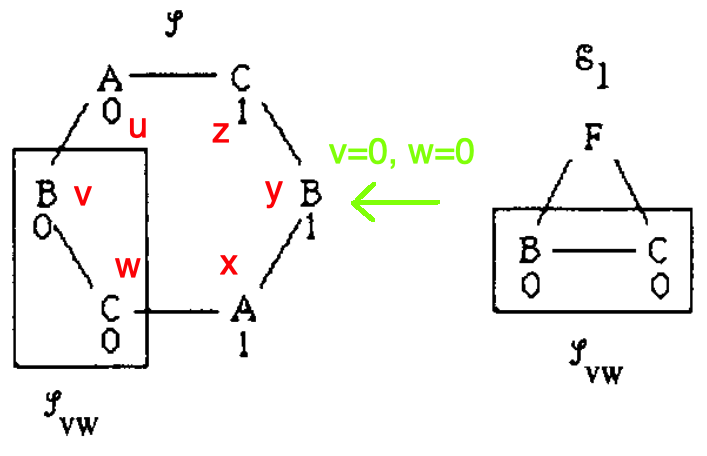

In this scenario the behaviors of \(v,w\) correspond to the behaviors of \(b,c \in \mathscr{E}_1 \in\) P (running devices \(B,C\) with inputs \(0,0\)). Node \(a\) runs a device \(F\) that mimics node \(u\) talking to \(v\) when talking to \(b\) and node \(x\) talking to \(w\) when talking to \(c\) (using the Fault axiom). Note that what’s crucial here is that node \(a\), being faulty, can report differing values to nodes \(b,c\). Despite this subterfuge nodes, by validity of P, \(b\) and \(c\) both commit to 0. By the locality axiom, the scenario \(\mathscr{E}_1\) in the three node system is identical to the scenario \(\mathscr{L}_{v w}\) in the six node system. Therefore, since \(b,c\) both commit to 0, so do \(v,w\).

Scenario 2

In this scenario the behaviors of \(w,x\) correspond to the behaviors of \(c,a \in \mathscr{E}_2 \in\) P (running devices \(A,C\) with inputs \(1,0\)). Now node \(b\) is faulty. Hence, \(b\) mimics \(v\) talking \(w\) when talking to \(c\) and mimics \(y\) talking \(x\) when talking to \(a\). Again by the locality axiom, since the behavior of \(c\) is identical to that of \(w\), it chooses 0. By agreement of P (\(a,c\) are the correct nodes and therefore have to agree) node \(a\) switches from 1, choosing 0 and therefore node \(x\) chooses 0 as well.

Scenario 3

In this scenario the behaviors of \(x,y\) correspond to the behaviors of \(a,b \in \mathscr{E}_2 \in\) P (running devices \(A,B\) with inputs \(1,1\)). Now node \(c\) is faulty. Hence, \(c\) mimics \(w\) talking \(x\) when talking to \(a\) and mimics \(z\) talking \(y\) when talking to \(b\). Validity requirements (if all correct nodes have the same input then that input must be chosen) require that nodes \(a,b\) choose 1. Thus \(x,y\) also choose 1. But as we saw in scenario 2, \(x\) must choose 0 for this set of inputs (and corresponding conditions imposed by \(\mathscr{E}_2\)). Therefore a contradiction.

Extending this argument to argument to arbitrary \(n\) is left as an exercise to the reader 😊 (hint: group nodes in three sets \(a,b,c\) such that each has at least one node and at most \(f\) nodes).

Upper bound without digital signatures (for broadcast)

We prove that the \(n/3\) is actually tight i.e. that if \(f > n/3\) are corrupt then Byzantine broadcast is impossible.

In this protocol every node maintains a sticky bit whose value is in the set \(\{ 0,1,\bot\}\) which reflect that node’s current belief about the consensus (\(\bot\) indicates that the node is agnostic). Initially the designated sender’s bit is its input bit and everyone else’s is set to \(\bot\). In the first iteration the designated sender is the leader but for every following round a random node \(L_r := H(r)\) is elected a leader using a random oracle7 \(H\). The protocol proceeds in three for every iterations \(r = 1, \dots, k\):

- Round 0: Leader \(L_r\) sends a proposed bit \(b\) to everyone, where that \(b\) is chosen as follows

- If \(L_r\)’s sticky bit is not \(\bot\) then \(L_r\) send that sticky bit

- Otherwise \(L_r\) chooses \(b \in \{0,1\}\) uniformly randomly

- Round 1: A vote on a bit \(b'\) is held and then broadcast to everyone

- If a node’s sticky bit is not \(\bot\) then the node chooses \(b'\) to be that bit

- Otherwise the node chooses the \(b\) proposed by \(L_r\) in round 0

- Round 2: All nodes tally the votes they received

- If a node tallies the votes such that \(2n/3\) of the votes are for the same bit \(b'\) then that node updates its sticky bit to be \(b'\)

- Otherwise the node updates its sticky bit to be \(\bot\)

Finally (after \(k\) iterations) everyone votes their sticky bit.

We now prove Byzantine broadcast for this protocol. Henceforth assume \(f > n/3\).

Lemma 3: In any iteration \(r\) it cannot be be that honest nodes disagree on \(2n/3\) of the vote.

Proof: Suppose some honest node \(i\) tallies votes from \(2n/3\) nodes \(S_i\) for \(b\) and \(j\) tallies votes from \(2n/3\) nodes \(S_j\) for \(\neg b\) (not \(b\)). But \(\lvert S_i \cap S_j \rvert \geq n/3\) (pigeonhole principle) and thus there must be at least one honest node in \(S_i \cap S_j\) and this node voted both \(b\) and \(\neg b\) (which is a contradiction).

Corollary: two honest nodes can’t have “opposing” sticky bits \(b\) (though two nodes can have \(b\in \{0,1\}\) and \(b' = \bot\)).

An iteration \(r\) is called lucky if \(L_r\) is honest and no node has \(\neg b\) bit wrt the bit \(b\) that \(L_r\) proposes (in that round).

Lemma 4: Suppose that iteration \(r \leq k\) is lucky and \(L_r\) proposes \(b \in \{0,1\}\) in iteration \(r\). Then every honest node’s sticky bit at the end of the protocol must be \(b \in \{0,1\}\).

Proof: In iteration \(r\), every honest node must vote on \(L_r\)’s \(b \in \{0,1\}\). Thus, every honest node will receive at least \(2n/3\) votes for \(b\) in round 2 of the iteration. By Lemma 3, no honest node sees \(\neg b\) from \(2n/3\) nodes in this same iteration. Hence, every honest node will set its sticky bit to \(b\) in iteration \(r\) and therefore in iteration \(r+1\) (and \(r+2, r+3, \dots, k\)) all nodes will vote \(b\) as well.

Lemma 5: Suppose the choice of random oracle is independent of the choice of corrupt nodes. Then, for every \(1 \leq r \leq k\), even when conditioned on whether prior iterations are lucky or not, the \(r\)th iteration is lucky with probability \(1/3\).

Proof: In every iteration, if \(L_r\) is honest and its sticky bit is not \(\bot\) at the beginning of iteration \(r\), then the iteration is guaranteed to be lucky due to Lemma 3. Conditioned on \(L_r\) being honest and its sticky bit being \(\bot\) at the beginning of iteration \(r\), the iteration is lucky with probability at least \(1/2\) (depending on whether \(L_r\)’s random choice coincides with the sticky bit of the honest nodes). Therefore, conditioned on \(L_r\) being honest, iteration \(r\) is lucky with probability with \(1/2\). Notice that every iteration has an honest leader with probability \(2/3\) (since the leader is randomly chosen). Thus, iteration \(r\) is lucky with probability at least \(\frac{1}{2}\cdot \frac{2}{3} = \frac{1}{3}\).

Lemma 6: There is a lucky iteration with probability \(1 - \left(\frac{2}{3}\right)^k\).

Proof: By Lemma 5 the probability that any particular iteration is unlucky is \(1 - \frac{1}{3} = \frac{2}{3}\). Therefore the probability that all iterations are unlucky is \(\left(\frac{2}{3}\right)^k\).

By Lemma 4 and Lemma 6 we have probabilistic Byzantine broadcast.

Footnotes

-

The only difference between agreement and broadcast is absence of a sender in agreement (i.e. honest nodes need only agree with each other and if their inputs agree then they must output those inputs). ↩

-

The state of every node and edge in the graph or subgraph throughout the course of the protocol. ↩

-

The behaviors of the nodes and edges in the subgraph. ↩

-

A primitive that takes a bit as input and returns a bit as output according to the protocol. ↩

-

A graph \(S\) covers \(G\) if there is a mapping \(\phi: S \rightarrow G\) that preserves neighbors. ↩

-

A random oracle is a function that deterministically gives you a random answer i.e. “it knows a random answer for every question”. One way to implement a random oracle is to use a hash function \(H: \{0,1\}^* \rightarrow [n]\). ↩